- Home

- Annabel Port

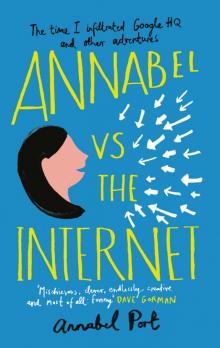

Annabel vs the Internet

Annabel vs the Internet Read online

Dear Reader,

The book you are holding came about in a rather different way to most others. It was funded directly by readers through a new website: Unbound. Unbound is the creation of three writers. We started the company because we believed there had to be a better deal for both writers and readers. On the Unbound website, authors share the ideas for the books they want to write directly with readers. If enough of you support the book by pledging for it in advance, we produce a beautifully bound special subscribers’ edition and distribute a regular edition and ebook wherever books are sold, in shops and online.

This new way of publishing is actually a very old idea (Samuel Johnson funded his dictionary this way). We’re just using the internet to build each writer a network of patrons. At the back of this book, you’ll find the names of all the people who made it happen.

Publishing in this way means readers are no longer just passive consumers of the books they buy, and authors are free to write the books they really want. They get a much fairer return too – half the profits their books generate, rather than a tiny percentage of the cover price.

If you’re not yet a subscriber, we hope that you’ll want to join our publishing revolution and have your name listed in one of our books in the future. To get you started, here is a £5 discount on your first pledge. Just visit unbound.com, make your pledge and type annabel5 in the promo code box when you check out.

Thank you for your support,

Dan, Justin and John

Founders, Unbound

For Mum and Dad

Contents

Introduction (or why I started doing all this)

Author’s Note

The Challenges:

1 To live without the Internet

2 To prove that Britain isn’t broken

3 To tackle the problems of the world economy

4 To achieve immortality

5 To help the Occupy protesters

6 To do something no woman has done before

7 To become a prepper

8 To sell myself to Google

9 To make London lovely again after the riots

10 To leak some confidential information

11 To become a top model

12 To create some conceptual art

Q&A 1: Questions you might be asking yourself

13 To write a biography of Simon Cowell

14 To get revenge

15 To become a brand ambassador

16 To re-enact a TV show

17 To stage some kind of reunion

18 To write and publish some erotica

19 To get nominated for an award

20 To invent a new kind of clothing

21 To campaign for a four-day working week

22 To have my portrait painted by a major artist

Q&A 2: More questions you might be asking yourself

23 To expose some Internet fraud

24 To bring the spirit of Brazil to the UK

25 To collect more tax from the super-rich

26 To befriend Vladimir Putin

27 To get an English Heritage blue plaque erected

28 To become the new CEO of Tesco

29 To overthrow something or someone

30 To create a rival to the Tour de France

31 To become a self-help guru

32 To debunk a scientific theory

The End (or why I stopped doing all of this)

About the Author

Acknowledgements

VIPs

Supporters

Copyright

Introduction

(or why I started doing all this)

I’m in a London Underground train carriage, surrounded by complete strangers, sitting in complete silence. We are between stops and trapped together. Trapped together underground. And I’m silently willing myself to break the biggest unwritten rule of the Tube: don’t talk.

I go to speak several times. I take a breath, and the words are ready. But I can’t do it. My mouth just won’t say them.

What is less welcome than a complete stranger on the London Underground, during the day – not even a drunken night, but during the day – turning to her fellow passengers and blurting out, “So, where’s everyone going, then?”

I take another breath, then clap my hands together.

“So, where’s everyone going, then?”

It is so excruciating that it’s like I’m having an out-of-body experience. I hear the words as I say them, but I don’t feel like they’re coming from my mouth. And I have no idea why my hands did that clap.

The three people opposite look at me with great surprise. Then one, a man in a suit, says, “Work.”

“Ooh. What do you do?”

He tells me he works in finance. He doesn’t want to talk to me. I can tell.

There’s a girl to his right. I say, “Are you off to work too?’

She tells me, “I’m at work now.”

This confuses me a bit as she’s eating peanuts and reading a book and I’m not sure that’s an actual profession, but I don’t want to start a row so I leave it there.

There’s a middle-aged man to my right who is stubbornly refusing to get involved, so I say to him, “Weather’s terrible, isn’t it?”

He ignores me. In case he’s hard of hearing, I say it again.

“Is it?” he replies.

I say, “Yes, have you not been outside today?”

I realise there’s a possibility that I might be starting to sound aggressive and we’re pulling into a station so I decide it’s time to get off.

I say, “Bye,” and the peanut lady gives me a lovely smile. I see what I strongly suspect is relief on the faces of all the others.

It was never my aim to demolish the wall of social constraint. It was the unexpected consequence of a big push from my friend Geoff.

I was working as a waitress in a cocktail bar when I met Geoff. Which is true, but mostly irrelevant to the story. In addition to living out the lyrics of an iconic eighties pop song, I was also doing work experience at a radio station where Geoff was a presenter. In my first two weeks, I spent eight solid days stuffing envelopes. Clearly, something about the way I handled those envelopes suggested to Geoff that I wasn’t achieving my full potential in life. I was also the first person he saw when his producer left suddenly and he urgently needed someone to answer the phones and make the tea on his evening show.

So I answered the phones and made the tea, and the evening show turned into a breakfast show, then a late-night show, then a drivetime show and somewhere along the way I’d become Geoff’s co-presenter.

I still wasn’t achieving my full potential in Geoff’s eyes, though. He thought I was in a premature middle age. No, that’s far too generous. A premature, deeply dull, very old age. The kind where you’re propped up with pillows in an armchair all day. He was mostly right. I live in a cul-de-sac. I like to watch episodes of Miss Marple. Probably the wildest thing I ever do is take a Sainsbury’s carrier bag to use in a Tesco supermarket. Very, very occasionally.

I’m also deeply lazy. I don’t know if there’s a lazy gene as I’ve never got round to googling it, but if there is, I’ve got it. When caught in the rain, it’s not uncommon for me to get soaking wet because I can’t be bothered to get my umbrella out of my bag. I did once summon the energy to paint the hallway of my flat, but it then took me another eight years to remove the masking tape. And that was only because I was moving out.

I haven’t always led such a plodding, mundane, lazy life. Before radio, before the cocktail bar, I’d lived abroad for three years, in Poland, Portugal and Mexico. Think how worldly I must be, that I took my unexciting life from the UK and replicated it somewhere else thousa

nds of miles away. I only went to avoid the effort of having to start a career.

I didn’t stray too far from the towns where I worked as an English language teacher. On one occasion in Poland, egged on by the other teachers, I took a trip to Krakow. The morning we were due to visit Auschwitz, I kept pressing snooze and missed the bus. If I’d gone abroad to find myself, I’d found that I was a terrible person.

I ended up coming home because, besides my friends and family, I missed British television too much. At least now I knew what I was looking for in life: a good crime drama.

So I came home, got a job in a bar and then a job in radio, and the rest of the time just settled in front of the television.

It’s understandable, then, why Geoff thinks I waste my life watching exciting things happen to other people. So he decided to set me various challenges, partly to give us something to talk about on the radio, partly for his own amusement, and partly with the belief that if he didn’t keep me busy, I’d get sofa sores.

Sometimes my comfortable, boring life felt infinitely preferable. Sometimes I would find myself being escorted out of a building by a Herculean security guard and wonder why I’d chosen to accept these challenges. Sometimes I looked back on that excruciating time I spoke to complete strangers on the Tube as a comparatively halcyon day.

But I am a bit less lazy now. And I did right a terrible wrong from years earlier. One sad summer, my parents, feeling sorry for me, asked if they could take me on a summer holiday to cheer me up. I said yes, picturing beaches and cocktails. It was a trip to Auschwitz.

That moment of chatting to complete strangers on the London Underground opened up a whole new world to me. It was like a wall inside of me had been knocked down. A wall built from titanium that had previously stopped me from being able to do things like start a light conversation on public transport. I even did it again the very same day.

I’m now on a Tube train where three people, all in their late twenties, are talking to each other.

Covertly listening in, I hear one of them say, “They’re charging 5p to print each copy.”

Feeling this is my cue, I ask, “What are you printing?”

The lady who’d spoken looks at me with a face that is difficult to describe. Imagine someone 60% horrified, 20% shocked, 10% disgusted, 5% freaked out and 5% angry, then multiply the intensity of that expression by about four. Now have that face stare at you in silence for five seconds before it speaks and says, “No, we’re not printing anything.”

This is confusing, but I feel a need to somehow redeem this situation. “Oh, it’s just that I know somewhere cheap,” I say, while thinking, Please don’t ask me where, I don’t know anywhere cheap, I just made that up, please don’t ask me where.

She doesn’t, and it’s very clear that my input in this conversation is no longer required.

People aren’t always friendly. And I’ve learned that I’m really bad at small talk. But strangely, I’d actually started to enjoy myself, living life one centimetre closer to the edge than before.

Author’s Note

The events described all took place sometime

between 2009 and 2014.

1

The Challenge:

To live without the Internet

Geoff thinks I’m a Luddite. I’m not. I’ve got no problem at all with mechanical weaving looms. And I’m not a technophobe. I own a mobile phone, digital camera, PlayStation 3, laptop, Sky box and microwave. But while this is all very useful information for anyone planning to burgle me, it doesn’t convince Geoff.

He feels that I’m not embracing the modern age, mainly because I’ve not yet joined Twitter. He suspects I think we were fine before all these newfangled things came along, so why do we need them now? There may be some truth in this.

He challenges me to find out if I’m right. To live without the Internet and prove that it’s not so great. That you can have the same experience of all these different websites, without ever going online. Then if a giant bug comes along and eats the Internet, who cares? We’ll all be just fine.

Part one: Celebrity gossip

I suspect that Tim Berners-Lee, when inventing the World Wide Web, didn’t intend for it to be used for celebrity gossip. Or maybe he did. Maybe he only invented it so he could keep regular tabs on Noel Edmonds. But I’m sure I can find out some red-hot celebrity gossip without having to use hugely popular sites like Heatworld and Perez Hilton.

I begin at lunchtime in London and I know exactly where all the celebrities are. The Ivy. The restaurant tucked away down a side street with the annoyingly opaque windows so you can’t see through to gawp at all the famous faces.

Obviously I’ve not got a table booked. That would’ve required a huge amount of forethought and an entry in the most recent Who’s Who. I have neither.

But the last time I went to a restaurant, I told the waiter who greeted me that I was meeting someone there, and then just went through to find them.

Admittedly that was Pizza Express, but I see no reason why I can’t do the same. Then I’ll have a good wander about, check out the toilets and, after making a spurious excuse, leave.

I’m genuinely pleased with this plan, so when I arrive I walk in with confidence.

The first thing I see is a lady in a cloakroom. They don’t have this at Pizza Express, but after giving the woman a smile intending to convey that I come here all the time and this is all perfectly normal, I pass through some more doors with purpose and find myself at the entrance to the dining area.

I can’t yet see through to the sea of celebrities as my view is blocked to my right by a bar and to my left by a man, who if I were at Pizza Express would be a waiter. But I’m not; I’m at The Ivy. He’s the maître d’ and he’s greeting me. I’m suddenly not sure it’s going to be that easy to breeze past him to my imaginary friend.

I say with as much confidence as I can muster, “Hello, I’m meeting someone here. Can I just go through?”

“Yes, of course,” he replies. Great, I think. Until he adds, “What’s the name of the person you’re meeting?”

This would be a good time to leave. I could feign amnesia or something that requires immediate medical attention. But not so immediate they need to dial 999. That would be a good thing to do. Instead I blurt out the first name that comes into my mind.

“Jo.”

“And their surname?” the maître d’ asks.

I could still get out of this. Amnesia is still an option.

“I’m not sure, actually, as it’s a client.”

I have never had a client in my life. I’ve only ever been a client myself at the hairdresser’s. I don’t know where this sentence has come from but it has now led the maître d’ to say, “Right,” and begin scanning the reservations book.

In my state of rising panic and silent prayers of, Please don’t let there be a Jo here. Please, I’ve not forgotten the purpose of my visit. I have a really good look at the book to see if I can spot a famous person.

I notice a Davina. But it’s not Davina McCall. I remind myself that celebrities don’t always use their real names and keep an eye out for a Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck, but there’s nothing.

These thoughts are interrupted by the maître d’ saying, “Oh, I’ve got a Jo Robinson. Is that who you’re meeting?”

This is not good. Really not good. The right answer to this question would be no.

“Hmmm,” I say. “Robinson doesn’t ring a bell.”

That should do the trick. I can be out of here in seconds.

But he has another question. “Was this arranged recently?”

“Erm, yes, I think it was yesterday.”

“I think it must be this one. Okay, follow me.”

Before I can make a last-ditch pretence of memory loss, I’m being whisked away and led through the restaurant. I’m in such an advanced stage of panic over what I’m going to do when taken to the table of this Jo Robinson, who I’ve never met before and is definitely

not meeting me for lunch, that I don’t even think to look around for celebrities.

I am sweating by the time we arrive at the table.

And it’s an empty table. An empty table for two. Jo hasn’t arrived yet. The relief is immense.

Within milliseconds, though, a waiter has appeared and is pulling a chair out for me to sit down, putting a menu in front of me and asking me what I’d like to drink.

I find myself saying, “I think I’ll just wait for my client to arrive.”

And I realise that a whole new horror has opened up to me. That Jo will eventually arrive and be shown to this table to find a complete stranger sitting there.

While I’m desperately thinking what to do next, I do take a few seconds to have a good look around me at all the celebrities. I’m not going through all this humiliation without some reward. I want to see Kate Moss playing footsie with Robert Mugabe, or Jude Law sharing a table, laid for two, with a teddy bear.

I don’t see this though. I see nothing. Not one celebrity.

The waiter is now bringing me a bread basket and a paper to read and I can endure this no longer.

I get up and head back towards the exit. I pass by the maître d’, who gives me a questioning look.

“I just checked my phone and realised I’m in the wrong place.” I tell him. “We’re meeting at Pizza Express.”

Internet 1, Annabel 0.

Part two: eBay

eBay is next. To emulate this, I need to sell some things I don’t want any more for the very best price. I go round my flat, looking for what I can turn into cold, hard cash.

In the kitchen, I find a Jamie Oliver Flavour Shaker, best described as a less effective pestle and mortar. I got it one Christmas, used it twice and then never touched it again. I brush the dust off and notice it’s got Jamie’s name on it, which is good as an autograph, so I can say it’s signed.

Annabel vs the Internet

Annabel vs the Internet